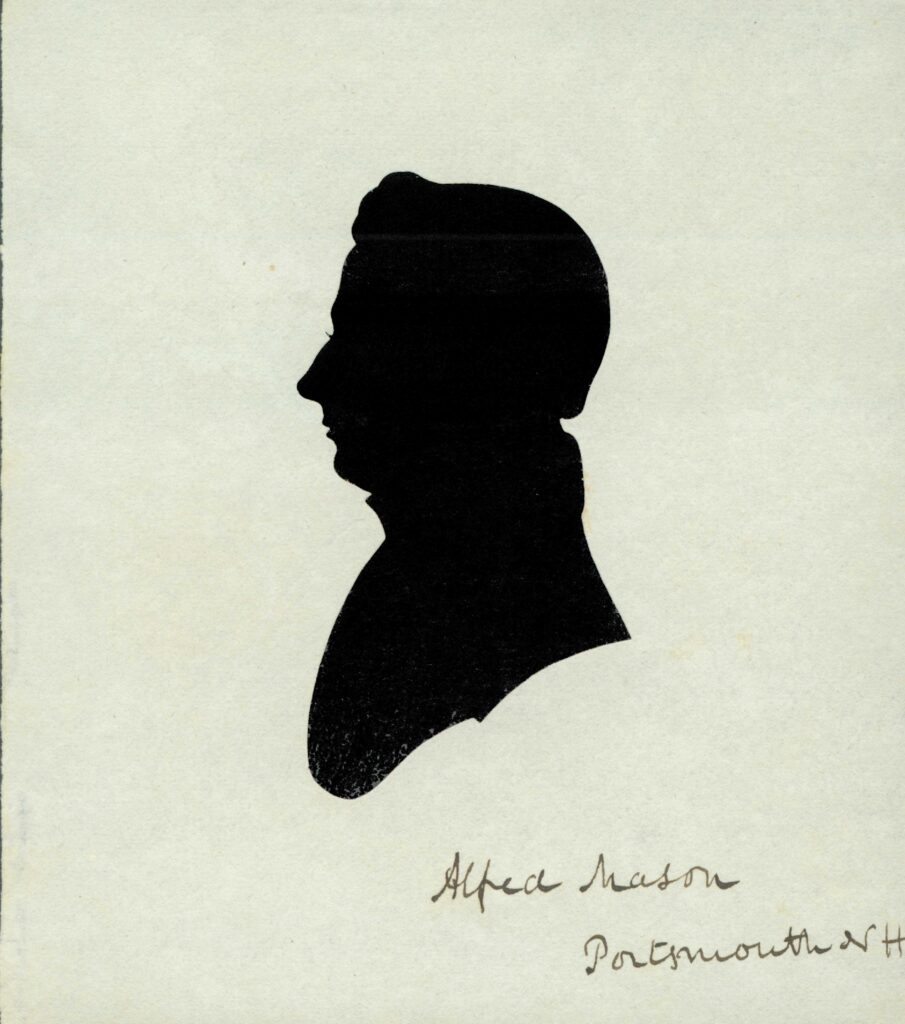

The Man of Science

Alfred Mason was born in 1804 at Portsmouth, New Hampshire. His mother was the daughter of a New Hampshire colonel and was beloved by her family. His father was Jeremiah Mason, a Portsmouth lawyer that a classmate claimed “never had a legal competitor and was colossal in intellectual and stature.” Mason grew up surrounded by wealth and influence that gave him a taste for the finer things in life. He was described as a docile, gentle child. At an early age, he developed an interest in science which was to define the rest of his life. For high school Mason attended Phillips Exeter Academy, where his classmates included William Hale, Jonathan Cilley, and Josiah Stover Little. All four men decided to attend Bowdoin for college.

When Mason was seventeen, he hopped in a stagecoach with his classmate Cilley to journey to Bowdoin. There he met Nathaniel Hawthorne, who became his roommate during his first two years at Bowdoin. The two remained friendly throughout their time at Bowdoin, although they came to travel in different social circles. Hawthorne found most of his friends in the Athenean Society, while Mason joined the Peucinian Society. Mason’s affluent background might also had made it hard for him to relate to the less privileged Hawthorne. After living with Hawthorne in Maine Hall during their sophomore year, Mason spent his final two years at Bowdoin boarding alone at Colonel Estabrook’s. Mason’s closest friend seems to have been George Washington Pierce, who glowingly described Mason as uniting “the most manly firmness and the noblest principles of honor, and the most lively and social disposition with the gentlest and warmest affections.”

Mason was a naturally intelligent and gifted student. He had a wide breath of general knowledge and was an eloquent speaker. His classmates acknowledged him as the “first talker” of the class who would not hesitate to speak up whenever he had an answer. Mason particularly shined in the realm of natural science. He boyhood passion for the subject matured into an adult obsession. Pierce described how Mason, “flung his arms around [science’s] inanimate form, and like Pygmalion’s statue, nature grew into life and beauty and intelligence beneath his warm embrace.” He was particularly passionate about physiology, natural history, chemistry, and mineralogy. Medicine also held his interest as he attended lectures at the Maine Medical School as a senior and post-grad. It is no wonder that his classmates and professors viewed him as a budding naturalist and the finest science student of the class.

Outside of the sciences however, academic life at Bowdoin held little interest for Mason. Early in his undergraduate career the young man concluded that the constant recitations and declamations that his professors required were not conducive to his learning. Beginning in the spring of his first year, Mason began to rack up a long list of fines for missing classes and worship. Occasionally he got in more serious trouble for whispering at prayers or for “disrespectful conduct” towards a college officer. Because of the low esteem in which he had held his academic obligations, Mason was not one of Bowdoin’s shining students. His reputation for brilliance was not reflected in his grades. At his senior class exhibition Mason was asked to give a conference with John S. C. Abbott and Cyrus Hamlin Coolidge on “The Characters of Luther, Calvin, and Knox as Reformers.” However, Mason was not asked to speak at Commencement nor given a class rank. Still, he graduated into the world with a bright future in science.

After leaving Bowdoin, Mason decided to pursue a career as a doctor. It was a natural consequence of his passion for physiology, chemistry, and medicine. Five other members of the Class of 1825 became physicians, but Mason stood out among them. He never pursued the career for financial gain, but rather because of his tremendous passion for science. A prominent scientist noticed Mason’s potential and sought to mentor him. Meanwhile, Mason moved back to Portsmouth to study medicine under a doctor named Pierrepont. He was a fast learner and quickly became the physician’s favorite pupil. Mason also took the time to give back to his New Hampshire community. He taught a botany class for young women at his local Sunday school. Mason was also remembered for his unusual kindness and charity to the impoverished patients he treated.

In 1827, Mason completed his education in New Hampshire and moved to New York City to begin practicing medicine. Bellevue Hospital had selected him for the competitive and prestigious position of assistant surgeon. However soon after he arrived in New York, an epidemic swept through the city and his hospital. Mason refused to shy away from its danger and threw himself into his work. A eulogizer reflected on “how kind, how faithful and vigilant he was, in the practice of his duties, amid the appalling scenes of suffering and death.” As the weeks wore on, overwork and anxiety weakened Mason’s immune system, and he caught the virus. Mason was quickly overcome by a fever, and died so fast that his family did not even have time to visit before he passed away.

Mason’s death was an occasion of tremendous grief for those who knew him. He passed away at just 24 and universally recognized as a young man of incredible potential. His friend Pierce published a bitter lament in the Portland Adventist about Mason right after he died. At his funeral, the Reverend Charles A. Cheever gave an address on Mason so powerful that he later published it as a book. Mason never had the opportunity to have children or publish any works of importance, but the legacy of the passionate and talented man of science lingered in memories of all who knew him.