Joseph Whipple’s A Geographical View of the District of Maine, with particular reference to its internal resources, including the history of Acadia, Penobscot river and bay, with statistical tables, shewing the comparative progress of the population of Maine with each state in the union. Bangor: Peter Edes, 1816.

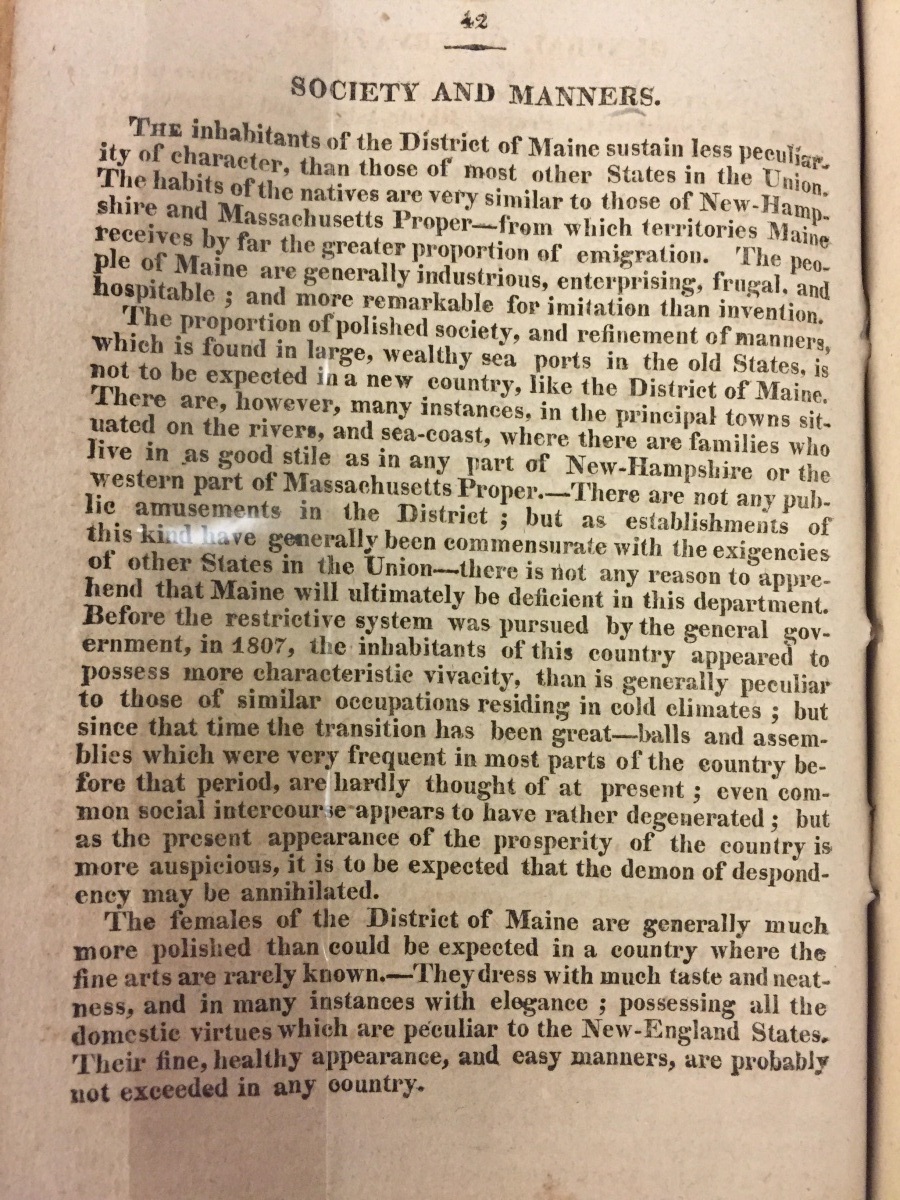

Women are rarely represented in the early printed records of Maine, and when they do appear it is often as pastoral beauties. Joseph Whipple, author of an early textbook about the state of Maine, characterizes women as “generally much more polished than could be expected in a country where the fine arts are rarely known. – They dress with much taste and neatness…Their fine, healthy appearance, and easy manners, are probably not exceeded in any country.” Whipple, of course, is interested only in white women of “polished society,” which he upholds as a marker for the territory’s success and worth. Such privileged inhabitants were confined to Maine’s few commercially successful communities along the coast and major waterways. Whipple tells his reader nothing of the women who occupy Maine’s many frontier-like settlements or provincial villages, nor the Native American and Black women who also comprised the area’s populace at the time. More recent scholarly research is helping to reveal some of this hidden history. We now know, for instance, that in 1829, 79 black women lived in Portland, representing the largest concentration of black women in any Maine town at this time. Maine becoming a state made little difference to Maine’s women, whether a part of Whipple narrative or not. As the new state constitution made clear, “every male citizen of the United States of 21 years and upwards, excepting paupers, persons under guardianship and Indians not taxed […] shall be electors.” Married women were under the authority of their husbands, a continuation of British Common Law adopted by Maine courts.