Bowdoin’s Special Collections & Archives recently received the medical library of Dr. John Hubbard (1794-1869), a prominent physician, governor of Maine representing the Democratic Party from 1850 to 1853, and father to Thomas Hubbard, Bowdoin class of 1857 and namesake of Hubbard Hall. The collection is a gift of the Hubbard Free Library in Hallowell, Maine, where Hubbard practiced medicine for nearly 40 years.

Containing more than 260 volumes, Hubbard’s library offers a window into the life and work of a 19th century physician operating a solo practice in a bustling town. The books in his collection range from the very practical—anatomical and surgical manuals—to philosophical ones about the classification of epidemical diseases. Some of the oldest (1793) and most recent (1866) imprints concern women’s reproductive health, as do numerous others, pointing to the frequency with which Hubbard attended to obstetrical work. His library suggests he also made every effort to keep up with the most recent developments in his field. Hubbard subscribed to the American Journal of Medical Sciences and continued to acquire new publications throughout his life, including those on the burgeoning use of ether, magnetism, and electricity in medical care.

Upon his death, his medical office was sealed, and it remained a virtual time capsule for more than a century. His books were eventually transferred to the Hubbard Free Library in Hallowell, but never cataloged. In 2019, the trustees of the library voted to transfer them to Bowdoin College, partially in recognition of the Hubbard family’s strong connections with the College but also as a means of recognizing Bowdoin’s important role in Maine medicine.

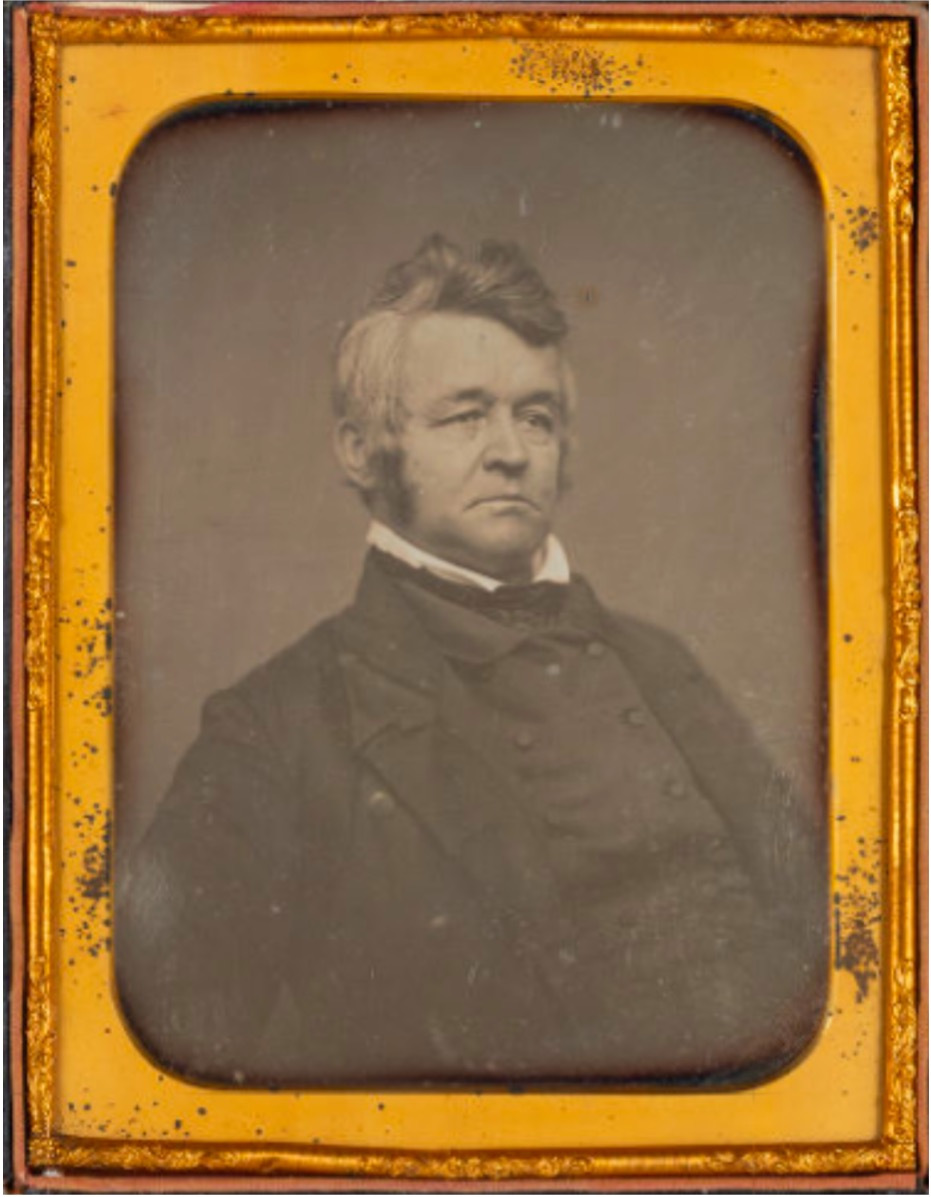

Dr. John Hubbard (1794-1869)

Born in Readfield, now Maine, then Massachusetts, in 1794, Hubbard graduated from Dartmouth and studied medicine at the Jefferson Medical College in Philadelphia. Upon graduation in 1822, he set up a doctor’s office in rural Virginia. According to a political broadside announcing Hubbard’s nomination for governor of Maine in 1849, it was his time in Virginia that awakened Hubbard’s anti-slavery sentiments. In Virginia, he had the opportunity “to see and feel the evils of slavery; and being convinced of its unfavorable influence upon a family, he determined, after a ten-year residence in a slave state, to leave it, and to settle where slavery did not exist.”

After leaving Virginia, Hubbard returned to Philadelphia for a year of post-graduate study in medicine. After brushing up on the latest developments in the field, Hubbard departed for Maine, settling with his wife and young daughter in a rambling wood frame house on Winthrop Street in Hallowell. Several more children would follow, including Thomas, the youngest, in 1838. With both his home and business thriving, Hubbard built a small outbuilding to serve as his doctor’s office, which contained both his medical tools and library. Hubbard was said to keep four horses fully occupied and often exhausted, as he traveled upwards of 75 miles in a day to attend to his patients, rushing out at all hours of the day and night. He was well regarded by his peers and considered among Maine’s foremost medical experts of his time, with other physicians seeking his counsel on their most complicated cases.

Hubbard balanced his robust medical practice with growing political ambitious. In the 1840s, he was elected to the Maine Senate, and from 1850 to 1853, he served as Governor of Maine, representing the Democratic party that adopted a “Free Soil” platform seeking to block the expansion of slavery into the Western territories. “I am opposed to slavery in all its bearings, moral, social, and political,” Hubbard stated at the time. As governor, Hubbard also concerned himself with matters of public health and social services. He advocated for a reform school, a women’s college, and for public support for the state’s academies and colleges. His most controversial act—signing the “Maine law,” the nation’s first law banning the production and sale of alcohol—likely doomed his chances of re-election. Hubbard retired from political life in 1853 to focus on his medical career. He died in 1869, after suffering a stroke while riding in his carriage, perhaps to see a patient.