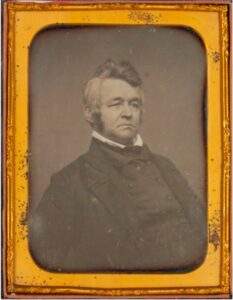

Bowdoin’s Special Collections & Archives recently received the medical library of Dr. John Hubbard (1794-1869), a prominent physician, governor of Maine representing the Democratic Party from 1850 to 1853, and father to Thomas Hubbard, Bowdoin class of 1857 and namesake of Hubbard Hall. The collection is a gift of the Hubbard Free Library in Hallowell, Maine, where Hubbard practiced medicine for nearly 40 years.

Containing more than 260 volumes, Hubbard’s library offers a window into the life and work of a 19th century physician operating a solo practice in a bustling town. The books in his collection range from the very practical—anatomical and surgical manuals—to philosophical ones about the classification of epidemical diseases. Some of the oldest (1793) and most recent (1866) imprints concern women’s reproductive health, as do numerous others, pointing to the frequency with which Hubbard attended to obstetrical work. His library suggests he also made every effort to keep up with the most recent developments in his field. Hubbard subscribed to the American Journal of Medical Sciences and continued to acquire new publications throughout his life, including those on the burgeoning use of ether, magnetism, and electricity in medical care.

Upon his death, his medical office was sealed, and it remained a virtual time capsule for more than a century. His books were eventually transferred to the Hubbard Free Library in Hallowell, but never cataloged. In 2019, the trustees of the library voted to transfer them to Bowdoin College, partially in recognition of the Hubbard family’s strong connections with the College but also as a means of recognizing Bowdoin’s important role in Maine medicine.

Benjamin Rush’s "An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, as it appeared in the city of Philadelphia, in the year 1793." Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, [1794].

Benjamin Rush (1746-1813) was a physician, a civic leader in Philadelphia, and a signer of the United States Declaration of Independence.

In 1793, after over thirty years without an outbreak, yellow fever hit Philadelphia killing thousands of residents in a span of just a few months: the total number of cases was estimated to be approximately 11,000 with a mortality rate for the city of 10%. As a professor of clinical medicine at the University of Pennsylvania, Dr. Rush observed the symptoms and spread of the disease closely, hoping to uncover some definite cause and means of prevention. Rush kept meticulous notes about his individual patients as well as about conditions in the city for many years. His notes ranged from the observation that “A meteor was seen at two o’clock in the morning, on or about the twelfth of September” to several remarks that “Moschetoes” were “uncommonly numerous.”

Rush, however, did not seem to draw any conclusions about the presence of the mosquitoes in relation to yellow fever. He favored the “miasma” (pollution) theory of the disease that was widely accepted at the time. In 1793, its proponents blamed the yellow fever epidemic on the miasma from a shipment of rotting coffee that had been dumped at the docks.

![Benjamin Rush’s "An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, as it appeared in the city of Philadelphia, in the year 1793." Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, [1794]. Benjamin Rush’s "An Account of the Bilious Remitting Yellow Fever, as it appeared in the city of Philadelphia, in the year 1793." Philadelphia: Thomas Dobson, [1794].](https://sca.bowdoin.edu/medical-school-of-maine/wp-content/uploads/sites/30/nggallery/dr-john-hubbard-his-medical-library/rush.jpg)